Just the facts about Inyo County

Inyo County was named after the Inyo Mountains which in Paiute means “dwelling place of the Great Spirit.”

Inyo County was established in 1866 from territory taken from Mono and Tulare counties. It was to have been called “Coso County” but that never occurred. Instead, Governor Low created “Inyo County” from the same land.

County seat……………………………………………………………………………………………….. Independence

Population……………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 17,980

Land Area (sq. mi.)……………………………………………………………………………………………….. 10,142

Highest Elevation……………………………………………………………………………………………… 14,492 ft.

Lowest Elevation…………………………………………………………………………………………………. -282 ft.

Distance between highest and lowest points……………………………………………………………… 80 mi.

Land in federal ownership…………………………………………………………………………………………. 92%

Land in state ownership…………………………………………………………………………………………… 3.9%

Land in City of Los Angeles ownership…………………………………………………………………….. 3.9%

Land in private ownership………………………………………………………………………………………… 1.7%

Average Climate

Owens Valley

Summer High…………………………………………………………………………………………………. 98°

Winter Low……………………………………………………………………………………………………. 22°

Death Valley

Summer High……………………………………………………………………………………………….. 115°

Winter Low……………………………………………………………………………………………………. 37°

Major Highways

U.S. 395 (south to north) San Bernardino County to Mono County

U.S. 6 (west to east) – Bishop to Province, Mass.

CA-168 – (west to east) – Big Pine to Nevada through Death Valley

CA-136 – (west to east) – Lone Pine to Nevada through Death Valley

The Owens River weaves Inyo and LA together

Owens River near Bishop.

The Owens River is famous the world over for its unique place in history as the lifeblood of both the Owens Valley and the City of Los Angeles. It was the diversion of its water to the great metropolis through the LA Aqueduct in 1913 that allowed that city to grow from just 100,000 people in 1900 to 1.2 million just 30 years later. In the Owens Valley, the completion of the aqueduct changed the valley’s history and signaled the beginning of a rocky and often contentious relationship with its “absentee landlord,” the City of Los Angeles.

Before the aqueduct, the Owens River served the area’s first inhabitants, the Paiute/Shoshone people quite well. They built small diversion dams to irrigate stands of native plants. The arrival of white settlers put an end to the Paiutes’ way of life. Ranchers quickly diverted Owns River and its tributaries for their own use, primarily to grow hay for their cattle. Farmers moved in and took the best land for themselves. Increasing numbers of white settlers made it nearly impossible for the Paiute to maintain their traditional way of life.

At its peak, farmers and ranchers in the Owens Valley had almost 60,000 acres of land under irrigated cultivation. When Los Angles officials arrived in 1905, it was the water rights of these farmers and ranchers that the City quickly pursued. Many sold out. Others held on but eventually caved in to the financial and social pressures put on them by the City. Once the LA Aqueduct was complete and diversions started in 1913, the loss of water and the impacts it had on Inyo were profound. Today, less than 15,000 acres of land in Inyo County are being irrigated.

The Owens River begins on the icy slopes of the Eastern Sierra just south of June Mountain Ski Area. Small creeks combine in Glass Creek Meadows to form Glass Creek, the furthest natural reach of this over-utilized watercourse.

Glass Creek soon joins Deadman Creek and flows easterly under US Highway 395 just before the climb to Deadman Pass. These two creeks are joined by smaller tributaries and springs and together they soon flow into the northern reaches of the broad expanse of Long Valley where it becomes well known to anglers as the “Upper Owens.”

For 26 miles, the Owens River winds its way through this picturesque setting toward 50-plus square mile Crowley Lake, the largest storage reservoir on the Owens. Fly-fishing is the sport here with brilliant rainbows, brown trout, and cutthroat testing the skills of anglers. From Crowley Lake, the Owens River drops steeply through the voluminous Owens River Gorge.

The steep vertical walls of the Gorge attract climbers from throughout the world and foot trails wind throughout the Gorge providing numerous hiking opportunities, especially during the cooler months.

As the Owens River enters the flats of the Owens Valley, its speed slows as it makes its way peacefully through the bottomlands. About 10 miles south of Big Pine, at a location called Aberdeen, the River is diverted into a the Los Angeles Aqueduct and from here, flows 233 miles to Los Angeles through a series of siphons, canals, pipes and reservoirs, entirely by gravity. It was and still is considered a marvel of engineering.

In 2006, after years of negotiations and litigation, the City of Los Angles agreed to allow water to flow on a permanent basis, down the 63 miles of the Lower Owens River dry riverbed below the Aberdeen diversion, all the way to Owens Lake

Dry Owens Lake itself is seeing a resurgence. For decades the dry lake fouled the local air with huge dust storms. Since 2001, the city of Los Angeles has been working under a court order to reduce the dust, and has cut the dust emissions coming off the lake by 95 percent. Shallow pools of water have been spread over much of the lake, providing a surge in visits by waterfowl. The City recently opened its Owens Lake Trails project. Three different access points provide 4 miles of hiking trails, taking in the scenery and providing wildlife-viewing opportunities.

The Owens River has had a long history of serving humankind, and continues to go through many changes as it works hard to please everyone. Perhaps the Owens can be best summed up in a Mark Twain quote, “A river is like a book, but not a book to be read once and thrown aside, for it has a new story to tell every day.”

Inyo waters are teaming with trout.

Inyo County anglers are not shy about sharing their favorite fishing spots. These locations can provide fun for the whole family since they also offer a variety of other activities besides fishing.

Diaz Lake – Created when an 1872 earthquake opened a depression in the earth 3 miles west of Lone Pine. The location of the Early Opener Trout Derby every March. Birding, camping, fishing, hiking.

Billy Lake, Independence – Created in 1872 similar to Diaz, now a wetland home to numerous birds and wildlife. Popular for warm-water fishing. Bird- ing, wildlife viewing, fishing, hiking, hunting, photography.

Mt Whitney Fish Hatchery, Independence – A French tudor structure built in 1916 resulted from a fish and game commissioner’s order for a building “to match the mountains… last forever… and be a showpiece for all time.” Now closed due to damage from a mudslide, visitors can enjoy the scenic grounds and in the summer months tour the building. Birding, wildlife viewing, camping, hiking, motor touring, pho- tography and mountain biking.

Tinemaha Reservoir, Big Pine – One of Inyo County’s best locations to view waterfowl and shorebirds… ducks, geese, American white pelicans and bald eagles (seasonally). Tule elk graze west of the reservoir. Thousands of trout are planted here each year, plus largemouth bass, bluegill and channel catfish.

Bishop Creek Recreation Area, Bishop – Sloping canyons, moraines, cirques and sawtooth ridges. Bishop Creek, South Lake, Intake Two, Lake Sabrina and North Lake are prime fishing spots as soon as the snow melts (closed to fishing in winter). Birding, wildlife viewing, fishing, fall colors, bouldering/rock climbing, hiking, motor tour- ing, photography, spring flowers, cross-country skiing and snowshoeing.

Pleasant Valley Reservoir, Bishop – Still water fishing from shore and float tubes, year round. Each March, the Blake Jones Trout Derby provides an- glers with a chance to get on the water just before the opening of fishing sea- son. Birding, wildlife viewing, fishing, hiking, hunting, star gazing.

Owens River Gorge, Bishop – Feisty trout are caught in the bottom of the gorge, year round. Climbing, hiking, fishing.

‘Bird Watching’ in Death Valley’s Star Wars Canyon

A jet fighter on a training run with the mountains of Death Valley’s Star Wars Canyon in the background. Photo by Jon Cassell/Panamint Springs Resort.

Star Wars Canyon has become of the premier “bird watching” sites in Inyo County.

But the falcons, eagles and nighthawks flying through the canyon are not your standard feathered friends. As the canyon’s name implies, these “birds” and the rest of their flock are high tech fliers that roar thought the canyon at up to 500 miles per hour. These birds are combat jets and military aircraft that scream down and through this narrow canyon at the edge of Death Valley National Park in a blink of an eye. Or the blink of a camera shutter.

The canyon, officially named Rainbow Canyon is located just below Crowley Overlook off of Highway 190 on the west side of Death Valley National Park.

The overlook honors Father John Crowley, the “desert padre” who served and promoted Inyo County and Death Valley in the 1920s and ‘30s. That piece of history is not what draws the jet set folks to the overlook and the edge of the canyon. They come to wait sometimes hours and sometimes days to catch a glimpse and a photo of the military jets that race through the canyons on training missions.

The canyon is about 5,000 feet wide and about 5 miles long. That’s enough room for jet jockeys to put on a show. Sometimes the jets come screeching over the canyon rim and then “burn and turn” to give their fans a great scene. Sometimes the jets just blast through the desert air, focused on their mission.

The Air Force and Navy have been using Death Valley, Star Wars Canyon and much of southern Inyo County as a training area since World War II. The canyon is part of a restricted military airspace that is used for air-combat training, supersonic test flights and other training and flight operations.

The rise of social media has fueled the fame of Star Wars Canyon among aviation photographers and enthusiasts who enjoy the thrill of witnessing a modern flying machine moving and maneuvering at the speed of sound.

This group of four C-17 Cargo jets swarm over Death Valley’s Star Wars Canyon. Photo by Jon Cassell/Panamint Springs Resort.

The region’s numerous military bases provide a steady flow of jets. The aircraft cruising Star Wars Canyon can come from Naval Weapons Station China Lake, Naval Air Station Lemoore, Edwards Air Force Base, Fresno Air National Guard Base, and Nevada’s Nellis Air Force Base. Planes from foreign allies also are known to use the canyon for training.

Patience and some luck top the list of requirements for those seeking a peek at the military jets. The Air Force and Navy do not provide any indication of when their planes will be in the canyon. It is not uncommon for plane-watchers to spend the day atop the canyon and not see a single plane. But then there are days when what seems to be a steady stream of jets come over, through and around.

Besides the Crowley Overlook, there are two other nearby viewing points. Plus, Panamint Springs Resort is at the end of the canyon, which makes it another spot for plane-spotting.

The Air Force acknowledges the canyon’s link to the iconic Star Wars movie franchise by calling the canyon “Jedi Transition.” But almost everyone else calls it Star Wars Canyon. The canyon is on the other side of Death Valley National Park from where scenes from the first Star Wars movie were shot that portray the Skywalker family’s desert planet, Tatoonie. Instead, there is another, more specific reason pilots and plane spotters link this particular canyon to the first Star Wars movie.

The most cited reference to the movie is the final sequence when Luke Skywalker and his fellow X-Wing pilots drop into the trench of the Empire’s Death Star and maneuver through the narrow “canyon.”

Regardless of what plane spotters and the military call the canyon, the sight of a war plane twisting and turning through Star Wars canyon is an extraordinary, otherworldly experience.

An F-18 jet fighter pilot “turn and burns” through Death Valley’s Star Wars Canyon. Photo by Jon Cassell/Panamint Springs Resort.

Lone Pine offers plenty of appealing adventures

Mt. Whitney Sunrise

Inyo County visitors can spend an entire week’s vacation enjoying the many offerings the quaint town of Lone Pine has to offer. From world-class outdoor adventure to award winning museums, Lone Pine ranks at the top of attractions that appeal to everyone.

Hikers and climbers are drawn to the magic that is Mt. Whitney. Only 12 miles from downtown Lone Pine lays Whitney Portal, the starting point for those heading for the summit of tallest U.S. peak outside Alaska. Note, this is not a stroll in the woods. High altitude hiking (Mt. Whitney peaks out at 14,508 feet) can drain the most fit and experienced climber. Be prepared with water, food and extra clothing. The trek usually requires an overnight stay.

A camp store and outstanding café are found at the Portal, along with a Forest Service campground, an incredible waterfall, a fishing pond and Forest Service campground and shorter hiking trails that offer a good trek into the wooded Sierra. Additional campgrounds and RV parks also dot the area, providing many camping options that suit a wide variety of camping experiences.

The Alabama Hills National Scenic Area, located just outside of town on Whitney Portal Road offer a variety of outdoor options. Climbers can scale the landmark “Shark Fin.” Those seeking a less strenuous adventure can tour the many dirt roads to seek out great views of the towering Sierra and Mt. Whitney. An added bonus are the numerous rock arches located in the hills, which are ready made for photos. Camping is allowed in the Hills, which can accommodate tent campers and RV and car campers.

Anglers will find several opportunities to land the “big one” in the Lone Pine area. Tuttle Creek and Lone Pine Creek are located just on the edge of town and are well stocked by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. Just three miles south of Lone Pine is Diaz Lake. Fishing for bluegill, bass and brown trout is popular here.

The Museum of Western Film History contains world class exhibits depicting the important role Lone Pine has played in the production of Hollywood movies, film and commercials. The Museum contains an extensive collection of real movie costumes, movie cars, props, posters, and other memorabilia. This collection represents a history of western film and highlights those films made in the area in and around Lone Pine from the early days of the “Round Up” to the modern blockbusters of today such as “Iron Man.” While you’re here, don’t forget to make the short trip up Whitney Portal Road and take the Self Guided Tour of Movie Road to get a first-hand look at real shooting locations of a great many of the motion pictures filmed in the beautiful Alabama Hills.

Lone Pine is a full-service town, offering several excellent motels, restaurants, a variety of retail stores and many other visitor conveniences. The Interagency Visitor Center, located south of town at the intersection of Highways 136 and 395 is an excellent source of information as is the Lone Pine Chamber of Commerce, located on Main Street.

Enjoy Bishop’s Big Back Yard

Mt. Tom west of Bishop

Bishop’s setting is an irresistible draw to outdoor enthusiasts, artists and businesses alike. The town is world famous for its scenery, hiking, fishing, climbing, hunting, bakeries and for its mules. Bishop and its surrounding area is the primary commercial and population hub for Inyo County and west central Nevada.

The Bishop Mule Days Celebration is a six-day event taking place Tuesday through Sunday the week before Memorial Day on the Tri-County Fairgrounds in Bishop, California. The 14-show event showcases mules in English, Dressage, Driving, Reining and Youth competitions, with the top competitors vying for World Championships in all disciplines. The championships, comedy classes, packing contests and world class specialty acts all take center stage in multiple arenas Friday through Sunday. The world-famous Mule Days Parade on Saturday, is one of the largest non-motorized parades in the nation.

Grazing north of Bishop

Bishop also offers an abundance of outdoor recreation and cultural activities. Highway 168 travels deep into the Sierra Nevada Mountains, providing access to scores of campgrounds and trailheads. North Lake, South Lake and Sabrina Lake are all easily accessed from Bishop Creek Canyon, as are miles of some of the finest trout fishing streams in California.

A multitude of additional recreational areas are found in the Bishop area. Pine Creek, Rock Creek, the Owens River Gorge, Fish Slough and Pleasant Valley Reservoir are all less than 30 minutes from downtown Bishop.

Rock climbing has become another very popular form of outdoor recreation in the Bishop area. The “Buttermilks,” about 10 miles west of Bishop, offers excellent bouldering opportunities for everyone from beginners to climbers with the highest of skills.

The Paiute-Shoshone Cultural Center on West Line St reflects the history and culture of the Nuumu (Paiute) and Newe (Shoshone) people. The Cultural Center showcases the art and life way of these indigenous people, who have lived in the Eastern Sierra for thousands of years. Visitors to the Cultural Center will also enjoy cultural displays, collections of Native American artifacts, historical archives and media.

About five miles northeast of Bishop is Laws Railroad Museum. Located on the site of the former Laws Railroad station and rail yard, the land, 1883 depot, locomotive and rail cars, and other buildings were donated to Inyo County and the City of Bishop by the Southern Pacific Railroad in 1960. The museum is operated by the Bishop Museum and Historical Society. The Laws Museum also houses an extensive collection of natural, civic, literary and ecclesiastical artifacts and history of the Owens Valley.

You’ll find no shortages of services in the town of Bishop. With several hundred motel rooms, more than 30 restaurants and nearly 50 stores, you can rest assured that whatever your need, you’ll be able to find it in Bishop.

Owens Lake Garners International Shorebird Designation

The Sierra reflected in the “new” Owens Lake.

Just like the migratory birds, the accolades just keep coming to the Owens Lake.

Earlier this spring, the sprawling lake was named a prestigious Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network site of international importance. The designation was a confirmation of the stunning transformation of the once dry and dusty, 100-square-mile lake south of Lone Pine into a man-made haven for all manner of birds.

There are only 104 Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network sites. They stretch from the southern tip of South America to Alaska. The sites earn the designation based on the number of shorebirds they attract and the sites’ value with regard to providing critical habitat to the many species of migratory shorebirds. Some of those birds stop off at the Owens Lake to refuel while making mind-numbing, marathon migrations from South America to the Arctic. Upwards of 100,000 birds can convene on the lake at the peak of the migration seasons, according to local birders.

Birders on Owens Lake: Birders using binoculars and long camera lenses while observing birds on the Owens Lake. Photo courtesy Mike Prather

The Shorebird Reserve Network designation was announced during the 4th annual Owens Lake Bird Festival, earlier this spring. The event is sponsored by the Friends of the Inyo and attracted more than 140 birders from around the country to the Owens Lake and Lone Pine. The group reported festival goers recorded well over 100 different species of birds on the lake, ranging from falcons to ducks to swallows to avocets to grebes.

The new designation does not provide any legally binding protections. The group does coordinate conservation efforts and publicity as a way to protect declining shorebird habitats before they are damaged or destroyed. The Audubon Society has also recognized the importance of Owens Lake to migrating birds and other wildlife.

Those designations and recognition serve as a validation and commendation of the work done on the lake by several local conservationists, who have been documenting the lake’s bird populations for decades and advocating for the birds and the habitats that sustain them. Tom and Jo Heindel, of Big Pine, have been watching the lake and the birds since coming to the area in 1972. They are compiling a survey of every species of bird to visit Inyo County in the last 150 years. Mike Prather, of Lone Pine, got his first look at the birds on Owens Lake in 1985. Since then he has researched the bird activity on the lake and worked with all the groups involved in the lake’s revival, from the State of California to duck hunters to the Great Basin Air Pollution District to the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power.

In recent years, the West’s saline lakes, such as Owens Lake and the Great Salt Lake, have become important destinations for migratory birds as other lakes and wetlands have disappeared. The next threatened lake, according to conservationists and the Audubon Society, is the rapidly shrinking Salton Sea. That huge inland lake has been in decline for years and has been targeted for rehabilitation. The turnaround at the Owens Lake could provide a template for the Salton Sea and other western lakes, the Audubon noted.

Rob Clay, the director of the shorebird reserve network, noted that the years of work to bring bird life back to the lake was an example of how human welfare and conservation can be linked to create positive results for local residents and the environment.

Owens Valley residents are familiar with the story of the lake’s new life. The lake dried up in the 1920s because the Owens River, which used to feed the lake, was diverted into the Los Angeles Aqueduct, leaving the lake to slowly dry up. After a number of lawsuits and a resulting court order, in 2001 the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power began a massive, landscape-scale project to reduce the billowing dust that came off the lake. That project included planting vegetation or covering dust-generating areas with gravel or using shallow flooding to stop the dust. The shallow flooding almost immediately started attracting birds.

Eventually, about 55 square miles of the lakebed, or about half of the dry lake, had received some sort of dust “treatment.” After spending about $2 billion on the dust control project, the amount of dust coming of the lake had been reduced by 95 percent.

And the birds have returned.

Some of the participants on the Owens Lake during the fourth annual Owens Lake Bird Festival earlier this year. Photo courtesy Ben Wickman, Friends of the Inyo.

Everyone Loves a Parade

Photos from the Bishop Christmas Parade; the Independence 4th of July Parade; the Bishop Mule Days Parade; the Lone Pine Christmas Parade.

History Comes Alive In Independence

#18 at the Eastern California Museum

For years Independence has been considered by many travelers to be a place to pass by quickly on the way to greater destinations. But for those that take a moment to explore “Indy” and the surrounding area, a wealth of adventure, culture and history are soon revealed.

Independence is the county seat of Inyo County. Built in 1927, the magnificent Inyo County Courthouse sits grandly in the center of town, and is one of a select group of county courthouse listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Independence boasts one of the best collections of historic buildings in Inyo County. The Edwards House on West Market Street was built in the early 1860s. The adobe portion is the oldest structure still standing in Inyo County. The “Commander’s House” was originally built at nearby Fort Independence, also in the 1860s. Later chunks and portions of the original building were moved into town, and various additions and expansions were completed to create the two-story home that stands today.

Mary Austin lived in Independence for several years in a home on West Market Street and completed her book, Land of Little Rain, in this house in 1903. She went on to write dozens of novels and plays which earned her a well-deserved spot in the pre-WWII American literary scene. A California State historical marker in front of the private residence (not open to the public) describes her ties to the valley and town.

The Eastern California Museum, three blocks west of the courthouse, houses much of the region’s rich history. The museum displays a diverse collection of artifacts, historic photographs, an extensive Native American basket collection, mining and farming equipment, the history of Los Angeles and its aqueduct in the Owens Valley, a local history research library, the Mary DeDecker native plant garden and a bookstore. The recently restored Southern Pacific Locomotive #18, the narrow-gauge Slim Princess, is also on exhibit at the museum.

The Mt Whitney Fish Hatchery lies just three miles north of town. At the time of its construction, Fish and Game Commissioner M. J. Connell instructed his team “to design a building that would match the mountains, would last forever, and would be a showplace for all time.” The walls of the building are constructed using native granite collected within a quarter mile of the site. The massive walls are two to three feet thick.

Today the Hatchery and its beautiful grounds are operated and maintained by the non-profit Friends of the Mt Whitney Hatchery. The shady grounds and main pond are excellent for relaxing, a picnic, and fish viewing. Volunteers staff a gift shop and give tours inside the hatchery during the summer. This is an excellent place to stop and take a few minutes to enjoy the beauty and the history of the Eastern Sierra.

Independence is a great place to stop and spend a few hours or a few days. It has plenty of room for the soul to expand and the imagination to soar. From the clouds called the Sierra Wave to the brilliance of the night time stars, Independence is more than a rest stop. Independence is a place of quiet beauty that is rarely found, but can be greatly treasured. Come and discover for yourself the wonderful town of Independence.

Explore in All Directions from Big Pine

A Sierra scene above Big Pine

Big Pine is the hub for exploring some of the grandest areas in the region, from the Sierra Nevada in the west to the White Mountains in the east.

In the center of town is Crocker Street, which heads west and climbs into the Sierra. The road ascends the mighty Sierra escarpment and enters Big Pine Canyon, winding along Big Pine Creek to campgrounds, cabins, a supply store, and a pack outfit for horseback excursions into the backcountry. At road’s end, lace up your hiking boots and head up trails that lead to unparalleled scenery and adventure including one of Big Pine’s several claims to fame: the Palisades Glacier, the largest glacier in the Sierra Nevada.

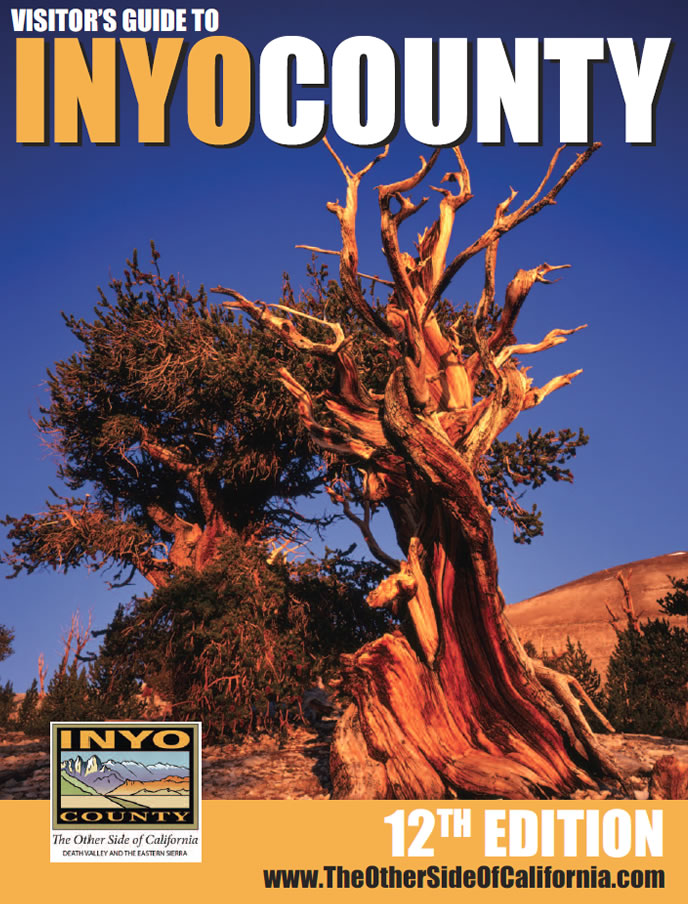

The Ancient Bristlecone Pine Forest, high in the White Mountains, is home to trees that are among the oldest living things on earth, dating to over 4,000 years old. A good paved road via Hwy. 168 leads to the Schulman Grove from the north end of Big Pine. A Visitor Center provides daily interpretive talks and natural history lectures mid-June through Labor Day. Three interpretive hiking trails lead visitors to close up views of these grand trees and stupendous views of the far off Sierras. Be sure and bring a camera for one-of- a-kind photos. Informative interpretive signs will help you understand the uniqueness of these noble trees as you meander along. Nearby Grandview Campground makes for a delightful base camp to explore the nearby region.

The Owens Valley Radio Observatory is located just a few miles northeast of town. These large white discs, seen from Hwy. 395 are owned and operated by Caltech and provides astronomers the ability to conduct extensive research of the stars and our solar system. Caltech offers occasional Open House events for the public to tour its fascinating research facilities.

Some of the Eastern Sierra’s finest fishing is found in and around Big Pine. Throughout the picturesque Big Pine Creek are numerous fishing spots, starting just a couple of miles outside town and continuing all the way to the end of the road 17 miles away. Close to town is the well-stocked Baker Ponds: turn west on Baker Creek Road, go about a mile to the campgrounds and from there the ponds are easy to find. The Owens River, about a mile east of Big Pine on Hwy. 168, abounds with trout and warm water species like catfish, bass and others.

There is also a “back road” to Death Valley National Park from Big Pine; be cautious, though, because the road is mostly of dirt and there are no facilities, but the scenery is wonderful and 75 miles farther is the north end of the Park near Scotty’s Castle.

The list of “things to do” while in Big Pine could go on and on. Take the time on your next visit to the Owens Valley to experience some of these world-class and one of a kind adventures with friends and family. They’ll provide memories for a lifetime.

Fall Colors Will Leaf you Happy, After a Little Extra Effort

Most visitors who drive up and down US 395 through Inyo County are impressed by the striking landscapes on both sides of the road. On one side is the dramatic upshot of granite peaks that make up the Sierra. Opposite the Sierra, subtle colors mix on the more rounded slopes of the White and Inyo mountains.

What many people aren’t able to see from the valley floor are impressive displays of fall colors when crisp autumn temperatures turn the leaves of cottonwood trees, aspens, willows and oaks into a vibrant explosion of shades of yellows, reds and green. That’s because those colorful sights hide a bit, in mountain valleys and lakes, from the casual observer.

That is one of several differences between the Eastern Sierra’s fall color season and the more well-known fall color hotspots, such as New England or the Rocky Mountains. Those regions’ entire mountain landscapes turns into sweeping, colorful sights. The wooded hills and mountains are covered completely with color.

In the Eastern Sierra, on the other hand, the leafy trees do not typically cover entire mountains. Instead, there are little stands and groves of trees at a certain range of elevation off the valley floor. Those higher-altitude trees turn colors first. Then, later in the fall, the big cottonwoods and other trees on the valley floor take their turn as colorful characters. That means Inyo County’s fall color season has a nice long run.

Another unique aspect to the fall color season is that for the most part the striking scenery can be viewed by simply driving up well-known local roads that reach into the high country. The key is to time the drive to match the colors.

For years, locals and late-season anglers and hikers pretty much had the colorful display of fall foliage to themselves.

But that little secret turned out to be hard to keep.

Transplants to California from more forested states who were tired of beach scenes and huge, green pine trees, tried to duplicate the leaf-peeping scenes they left behind. The Sierra, with its four season and mountains was an obvious place to look.

Once the word was out, all it took to transform a local tradition into a state-wide “must see” was a little promotion, a few years’ worth of Travel Section media coverage, and especially the proliferation of web pages, blogs and social media that made it easy for everyone to post dozens of stunning color photos. (The leading web page for fall color updates in the Sierra and throughout the state is still the first website devoted solely to fall color spotting, reporting and enjoying: www.californiafallcolor.com, with its catchy slogan, “Dude, autumn happens here, too.”)

Now, fall color is a “season” that occurs right after summer. Once the cooler weather arrives, so do eager leaf-peepers. Coming in cars or trucks, singly in or in groups, people start cruising the roads leading into the Sierra, from Cottonwood Pass to Bishop Creek. Some people are content to simply drive up and down the road and view the colorful sights from the comfort of their vehicle. Others get out and work their camera to capture the autumn scene before them.

The key to a successful search is to go slow and really look. While there are some places where large swaths of trees cover a large area, the smaller, more intimate stands of trees are just as compelling. A single stand of aspens in the middle of field of granite offers quite a sight. As does a stretch of willows alongside a stream. A cluster of color set off by a background of green pines offers an interesting contrast. The soft reflection of color in a small pond or lake can be a unique photo.

Another unique aspect to the fall color season is that it’s usually fairly easy to see Nature at work. Trees at higher elevations turn color first, then as time passes the wave of color literally moves down mountainsides and though valleys. So it’s not uncommon to start out seeing summer-green trees, then trees that have partly turned and finally get to trees in full color. It’s almost like you’re hot on the trail of fall color.

WHERE TO GO

In general, you can find fall colors in about any Eastern Sierra high country location in Inyo County. Well-known roads that lead to the backcountry typically move through the band of aspens, cottonwoods and willows that make up the best fall color viewing.

That means routes such as Cottonwood Pass and the Whitney Portal Road in the Lone Pine area will deliver you to fall color viewing. Likewise with Onion Valley Road out of Independence, and Glacier Lodge Road out of Big Pine.

Later in the fall, just the drive on US 395 will yield colorful sights as the trees along the valley floor put on a colorful show. Keep an eye out for tall, sprawling cottonwoods that stand by themselves in fields. When these individual trees turn, they are quite a sight. Trees in each town also turn later in the season, so go ahead and take a few minutes to drive through town toward the Sierra. In most cases, you will be able to see big, mature trees turning color with big Sierra peaks as a backdrop.

The Bishop Creek Drainage offers numerous fall color sights in a fairly compact area.

In early fall, North Lake is a landmark sight, and well worth the drive, since the road itself is flanked by tall, colorful aspens. The appropriately named community of Aspendell is a color oasis, as is the Cardinal Village, which you can see from the road above the tree-packed little canyon. Lake Sabrina has a couple of spots that are favorites, from the creek to the slow moving water and bridge just below the lake. The lake itself reflects Sierra peaks and blasts of color leading to those peaks.

The road to South Lake offers one of the longer, uninterrupted stretches of colorful trees decorating hillsides, ponds, an outstanding waterfall, and the meandering creek before reaching the lake itself.

Check www.californiafallcolor.com for the latest reports and fall color information.

After a roundabout trip, the Borax Wagons are Home at Laws

The two huge Borax 20-Mule Team Wagons and trailing water tank at the new barn at Laws Railroad Museum.

The instantly recognizable Borax 20-Mule Team Wagons took a bit of a roundabout route to their new home in an impressive, brand new barn at the Laws Railroad Museum and Historic Village.

The first leg of that journey involved nearly a decade of research and work and fundraising that eventually resulted in the construction of the huge, historically accurate wagons and the gear needed to hitch 20 mules to the two big freight wagons and the water tank rolling behind them.

Once the wagons were ready to roll in 2016, they were re-introduced to the public by rolling down some pretty impressive boulevards. First came the Pasadena Rose Parade, a California New Year’s Day tradition known around the world. Then the wagons and mules ventured through Washington, D.C. to help celebrate Independence Day on the National Mall in the nation’s capital.

While those parades have their fans and carry a tad of prestige in the world’s eyes, in the Eastern Sierra the crowning achievement of the 20-Mule Team Borax Wagons came when the whole outfit starred as one of the crowd favorites during several trips down Bishop’s Main Street during the annual Mule Days Parade.

The local pride came from two sources. First was the familiar face of longtime Eastern Sierra packer and teamster Bobby Tanner who helped bring the wagons back to life and personally maneuvers the huge wagons pulled by 20 mules, working two abreast, down the parade route. Second, the 20-Mule Team and Borax are both local products and local legends that contributed mightily to the notoriety and ongoing mystique of the Death Valley region, Inyo County’s premiere tourist attraction.

Finally, after dazzling yet another Mule Days crowd this year, the wagons headed for their new permanent home. On Memorial Day, May 28, a crowd of about 100 came to Laws to help dedicate the new, Borax 20-Mule Team Wagon Barn.

The big wagons were in the barn and, even without a cadre of mules, dazzled the crowd. The big, back wheels are 7-feet high. The wagon box towers above the big wheels. The wagons are made of a beautiful, lightly stained wood. In contrast, dozens of black bolts dot the wagon boxes in a testament to the authentic wagon-building trades that created the rolling historical replicas. The barn itself is first-class. The skylights in the roof send splashes of sunshine on the wagons. Long, white walls await additional photos and explanatory text. Those final touches will be added as time goes on, thanks to a collaboration between Laws and the Bishop-based American Mule Museum.

Besides those two local groups, the non-profit Death Valley Conservancy and Rio Tinto Borates (formerly Pacific Coast Borax), also played critical roles in bringing the 20-Mule Team back home to Inyo County.

Tanner addressed the crowd and recalled how, about 10 years ago, he contacted Howard Holland, the talented exhibit designer and board member of Laws Museum, with what Tanner called “a scheme” to build replica borax wagons. And now, after years of work and even more “scheming,” the wagons and their new home at Laws are a reality.

While touring the country with the wagons, Tanner said the real “eye opener” was that so many people, whether in Kansas, Ohio or Maryland, recognized the 20 mule team and wagons. Especially those from farm families or those who were familiar with mules, “knew exactly what they were looking at” when they approached the huge wagons. Part of the reason for the wagons’ notoriety, he added, came from “Ron Reagan” who hosted the TV show “Death Valley Days,” sponsored by Borax and featuring the wagons. Of course, “Ron” is also known as the former governor of California, president of the United States and, most importantly, one-time Grand Marshall of the Mule Days Parade.

While the 20-mule team can seem like “a local thing,” Tanner assured the crowd that “this is a significant deal,” and the Borax wagons and the 20-mule team is still “an American icon.”

Tanner then recalled how one man had an out-sized impact on the wagon project. In 1999, Rose Parade officials contacted Borax and asked if the company could bring the famed wagons and mules to the parade. The company had marketed “20-Mule Team Borax” from 1906 to1950. But most company officers did not want to revive the wagons.

But one corporate officer turned that thinking around and started the process to bring the wagons back, Tanner said as a way to introduce Preston Chiaro. He was managing the Boron mine at the time, and knew the Eastern Sierra. More important, he knew the Tanner family as the packers at Red’s Meadow.

He got the wagon idea turned around in the corporate offices. Then he was able to see the project through to completion since he eventually became president of US Borax, which was owned by Rio Tinto at the time – the most recent name for the Borax Company, which was known as Pacific Coast Borax when it built the first borax wagons to haul the mineral out of its Death Valley mines.

“These wagons have a real power,” Chiaro told the crowd. “It’s the power of an idea, and that idea is the development of the West.”

Chiaro noted that Rio Tinto put up a $150,000 challenge grant that made the fabrication of the wagons possible, along with the outpouring of support and donations from individuals and organizations. Another, even tougher obstacle was who could manage the mules and wagons. “Driving a 20-mule team was a lost art,” he said. Enter Bobby Tanner and his crew. Then came years of painstaking research followed by exacting construction and fabrication using 19th and early 20th century wagon-building skills and “technology.”

Once completed and rolling, Chiaro noted that a special aspect of the sight of the wagons in action is that “there is a beauty about it,” as 20 mules work in unison and respond to the commands of the teamsters. After watching the mules and wagons perform in parades large and small, Chiaro said it is easy to see the “magic” created by the imposing, vintage vehicles. “It sparks peoples’ imagination.”

And now, people can visit the wagons in their new, home barn at Laws, and let their imagination run wild.

Where to explore, recreate and be amazed in Death Valley and Inyo County

Inyo County is “The Other Side of California,” a vast expanse along the eastern edge of California that covers 10,000 square miles (16,000 sq. Km), an area greater than six U.S. states (VT, NH, NJ, CT, DL and RI).

Inyo County is a land of extremes. It claims the highest and lowest points in the 48-contiguous states, and the oldest trees in the world. You’ll find hot and cold, wet and dry, barren and lush, refined and common at different times and in different parts of the county.

The two most distinct aspects of Inyo County are Death Valley and the Eastern Sierra. Within these destinations are such natural wonders as Death Valley National Park, the Ancient Bristlecone Pine Forest, the Palisade Glacier, Mt. Whitney, Rock Creek Canyon, the High Sierra and a classic western landscape that has been seen in countless motion pictures. With six million acres (2.4 million hectares) of public land, Inyo County offers numerous opportunities to explore, recreate and be amazed.

Here is a brief rundown of what makes Inyo County so alluring:

DEATH VALLEY

In 1849, a party of pioneers nearly perished while attempting to cross this desert valley. Upon being rescued, one turned and exclaimed, “Goodbye, Death Valley,” so naming it. Today, a million people say hello to Death Valley National Park, each year. The national park is the largest in the lower 48 states at 3.3 million acres (1.3 million hectares), and with the southeastern corner of Inyo County, comprises more than half the landmass of the county.

Death Valley attracts photographers, rock hounds, hikers and geologists to its fascinating and austere landscape.

Favorite sights include the nine-mile, looping Artist’s Drive with its many-colored rock formations. Popular trails pass through the Golden Canyon, Mosaic Canyon and Wildrose Peak trail. Each of these leads to amazing views and other-worldly formations. The Badwater Basin salt pan is the lowest point in North America — 282 ft/86 m — below sea level, and the highest point in the national park is Telescope Peak at 11,049 ft./3,315 m.

Death Valley has more than its share of intimidating places: the Funeral Mountains, Rhyolite Ghost Town, Badwater, Stovepipe Wells, Salt Creek and Furnace Creek, among them. Yet, despite these notorious-sounding names, several species of wildlife inhabit the park and it’s so popular that for much of the year (late fall to late spring) available rooms and campsites are far and few between.

Park lodging centers at the Oasis (formerly Furnace Creek Resort) whose famous Inn was opened in 1927 by the Pacific Coast Borax Company of 20 Mule Team fame. The Furnace Creek Inn was meant to save the company’s failing railroad. As the value of mining faded, so did the railroad, but the Furnace Creek Inn thrived. It is today among the most highly sought and refined oasis to be found within the National Park System. Nearby The Ranch is a popular destination for families and RV campers. The park’s visitor center is located here and the Borax Museum displays artifacts, Borax wagons and other historic equipment from the park’s past.

Each season in Death Valley has its attraction. In winter, snowflakes tumble until they evaporate near the valley floor; near the end of winter, showy blooms of wildflowers appear; and in summer, temperatures often reach 120° F/49° C.

Stovepipe Wells – A motel, restaurant, pool, campground with RV sites and convenience store and gas station are located here. Old charcoal kilns and the ghost town of Leadfield are worth visiting.

Panamint Springs – They really mean it, when they say “Last Gas” at Panamint Springs at the national park’s western boundary. You’ll drive 30 miles before you find the next gas or water. Remember, you’re in Death Valley! Continue east on CA-190 to cross Towne’s Pass into Death Valley, south on CA-178 to Trona and west on CA-190 to Olancha and Lone Pine (CA-136).

Shoshone – This desert town to the southeast of the national park was once a railroad center and rest area for local miners. It still serves as a service hub with food, gas, lodging, supplies and RV sites.

Tecopa – Named after Paiute-Shoshone Indian chief, Tecopa was a hard-rock mining camp in the late 1800s, though today, it is best known for its hot springs. Natural hot water is contained in separate bath houses for men and women, with RV sites and a small store. A surprising sight in this desert is Grimshaw Lake, a favorite of water skiers. Nearby marshes attract migratory birds and were a stopping point along the Old Spanish Trail, a National Historic Trail that passes through Tecopa. A treat five miles south of Tecopa is China Ranch where you can buy all kinds of treats made from dates… date shakes, date baked goods and take your date on a hike beside the federally recognized Wild and Scenic Armargosa River. At Dumont Dunes, 4-wheelers, dune buggies and dirt bikes get airborne in the dunes and take more terrestrial tours through scenic canyons.

OWENS VALLEY

One of the earliest American explorers described the Owens Valley as containing “ten thousand acres of fine grass.” Today, it is mostly arid. As told in Marc Reisner’s book, Cadillac Desert this once-fertile farmland, populated with fruit trees, was the victim of California’s Water Wars of the 1900s in which water rights to the Owens River were obtained by Los Angeles. Today, a third of LA’s water comes from the valley through the LA Aqueduct. Court rulings and actions by the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power have helped restore fish habitat along the river, making it again one of the finest fly fishing streams in the West.

Bishop – Calling itself a Small Town with a Big Backyard, Bishop is the hub for recreation of all kinds, from rock climbing and bouldering in the famed Alabama Hills, to fishing in the Owens River, Bishop Creek Canyon (also a fall colors hotspot) and various local lakes. Bishop is also the jumping off point for hikers seeking the solitude of the numerous high Sierra trails that wander into the unspoiled wilderness west of town, which also provides dramatic backdrop and sunsets that cannot be forgotten.

The most populated town in Inyo County, Bishop also has the most number of accommodations and services. Bishop began as a ranching town. Later, ranches evolved into pack stations with their sure-footed mules carrying the gear of fishermen and campers back into the Sierra. If any animal expresses the heart of Inyo County, it is the hard-working, intelligent, yet stubborn mule, which is honored annually during Bishop’s “Mule Days.”

Long before the ranchers arrived, Paiute Shoshone people lived here. Their reservation sits northwest of town and the Paiute Palace Casino adds excitement to a stay in Bishop. Many of Bishop’s visitors include a stop at the Owens Valley Paiute Shoshone Cultural Center and Museum to learn about the first inhabitants of the area and to enjoy experiencing one of the tribe’s cultural events.

Today, Bishop is the center of operations for the largest public utility in the nation, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, which provides water and power to the nation’s most populated city and provides access to the streams it manages for fishing. Southern California Edison also got its start in Bishop, and continues to operate hydroelectric power plants in the Bishop Creek Drainage, and its efforts to dam up streams and enlarge natural lakes created a world-class string of fishing holes.

Big Pine – This small town prides itself on being a gateway to the majestic Sierra Nevada and White Mountains. Drive east and you find the Ancient Bristlecone Pine Forest. Drive west and you find trailheads that lead to the Palisade Glacier and Eastern Sierra. Outfitters run horse packing trips to remote alpine lakes. Numerous fishing holes are found along Big Pine Creek and the Baker Ponds. The Owens River teems with trout, catfish and bass.

Independence – The county seat since 1866, Independence is the center of regional history with its historic courthouse; the Edwards House, oldest structure in the county; the Commander’s House, a century-old Victorian home; the Mary Austin home (she wrote Land of Little Rain); and the Eastern California Museum, with its extensive exhibits, artifacts, photographs, native plant garden and historic mining and farm equipment. Good fishing is found nearby at Independence Creek, the Onion Valley and along the Owens River. With a name like Independence, it’s understandable why the town has one of the best Independence Day parades with traditional early morning flag raising, pancake breakfast, fun run/walk, small-town parade, homemade ice cream and pie social, kids’ games, an arts and crafts show, deep-pit barbecue and sunset fireworks show.

Lone Pine – One of the most filmed and photographed landscapes in the county is found surrounding Lone Pine. West of town are the Alabama Hills, named by locals who were Southern sympathizers during the American Civil War. This collection of irregular, ruddy, windswept boulders backed by a horizon of Sierra peaks, has been the backdrop for about 400 Hollywood films from “Gunga Din,” to “Gladiator,” to “Rawhide,” to “Iron Man.” It’s where Roy Rogers first mounted Trigger, where Tom Mix rode to the rescue and where Robert Downey Jr. got blown up. Lone Pine has been seen in so many movies, that it has commemorated its fame by hosting the annual Lone Pine Film Festival. The Lone Pine Museum of Western Film History preserves the motion picture history of Inyo County with film memorabilia, cars, western carriages and an 84-seat theater.

Manzanar National Historic Site – During World War II, about 10,000 people of Japanese ancestry, about 60 percent being American citizens, were brought here to the Manzanar War Relocation Center as part of the “war hysteria” and racism that swept America after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Manzanar was one of 10 Relocation Centers that eventually held about 120,000 people of all ages of Japanese descent for the duration of WW II. Finally, in the 1980s, the US government formally apologized to the internees for their imprisonment without charges. The site in now in the hands of the National Park Service. An interpretive center is located in the camp’s former auditorium, a number of replica barracks and buildings offer insights into camp life and a self-guided auto tours is offered.

EASTERN SIERRA

Mt. Whitney – On the east side of the Great Western Divide, Mt. Whitney stands 14,508 ft., the tallest mountain in the contiguous United States. Hikers reach the summit through Whitney Portal, 13 miles west of Lone Pine. It’s a 10.7 mile hike and requires planning, a wilderness permit and careful attention to advisories regarding the precautions of hiking at high altitudes, obtained within the Eastern Sierra InterAgency Visitor’s Center, south of Lone Pine.

Palisade Glacier – The southernmost glacier in the U.S. and the largest in the Sierra Nevada is located west of Big Pine and is visible from U.S. 395. The glacier sits at the base of Palisade Crest in the North Fork Basin. The scenery attracts hikers to trails that follow the ancient glacier.

Rock Creek Canyon – Between Bishop and Mammoth Lakes is picture-perfect Rock Creek Canyon. Rugged Eastern Sierra sawtooth peaks rise above emerald meadows, populated with fluttering aspens and cut my meandering clear streams.

Inyo National Forest and the John Muir Wilderness – For complete retreat, backpack or take a mule pack trip to the high country, to dozens upon dozens of remote glassine lakes with romantic names like Lake Helen of Troy, Elinore Lake, Moonlight Lake and the Treasure Lakes. You will understand why John Muir wrote, “Climb the mountains, and get their good tidings.” Few experiences are as emotionally satiating as being in the rarified air of the Eastern High Sierra in settings whose beauty defy description.

Sierra Bighorn Sheep – Three subspecies of bighorn sheep live in the United States. You can see two of them within minutes of one another in Inyo County, California. Sierra Bighorn can be seen in Eastern Sierra canyons. From U.S. 395, north of Bishop, follow Pine Creek Road through Round Valley. In the last couple of miles before the road ends, look up to the north to see the buff-colored coats of the Sierra Bighorn Sheep as they graze among pines and brush. You will be surprised how well they blend into the landscape and how difficult it is, at first, to see them. With practice, it becomes easier. There are no formal tours to see the bighorn, however the Bishop office of the California Department of Fish and Game can explain how best to see the elusive bighorns. Some tips: the Bighorn will not let you get closer than a couple of hundred yards, so bring powerful binoculars or a camera with a telephoto lens and enjoy seeing them from a distance.

WHITE MOUNTAINS

Ancient Bristlecone Forest – Thirty-six miles east of Big Pine in the White Mountains at elevations over 9,000 ft grow the oldest living trees. The oldest of them, Mehtuselah, is estimated to be nearly 4,800 years old. Several groves of the venerable trees can be seen. Exhibits at the visitor center at Schulman Grove describe the trees. From Big Pine, travel east on CA-168 to the Ancient Bristlecone Pine Forest Scenic Byway.

SOUTH COUNTY

Pearsonville – You’ve arrived in Inyo County, if traveling north on US 395 in a town often called the “Hub Cap Capitol of the World,” thanks to Lucy Pearson who for years collected a large collection of hubcaps and cataloging and storing each in a large warehouse. In Pearsonville, you’ll find gas, food, a towing service, wrecking yard and a ton of hubcaps!

Keeler – This was once the southern terminus of the Carson & Colorado Railroad. When service ended in the 1960s, most of Keeler’s residents moved away. The streets are mostly quiet and no services exist. However, if you have a 4WD vehicle, follow a dirt road east to Cerro Gordo, a ghost town with several well-maintained silver mine buildings and a small museum.

Olancha – This little ranching town has been a waystation since its inception in the 1860s. Cooling cottonwood trees and an inviting café attract travelers along US 395. Hikers and backpackers will often set off into the South Sierra Wilderness and onto the Pacific Crest Trail from nearby trailheads.

Darwin – Stop in Darwin and you won’t find any services, just a rich history, a hearty group of year-round residents and nearby Darwin Falls which begins as an underground spring that rises to the surface, spills over the falls and travels for a few hundred feet before disappearing again. Poke around Darwin and you’ll find old mines off dirt roads leading from CA-190.