Owens Valley

One of the earliest American explorers described the Owens Valley as containing “ten thousand acres [40 km²] of fine grass.” Today, it is mostly arid. As told in Marc Reisner’s book, Cadillac Desert and depicted in the motion picture, Chinatown, this once-fertile farmland, populated with fruit trees, was the victim of California’s Water Wars of the 1940s in which water rights to the Owens River were obtained by Los Angeles. Today, a third of LA’s water leaves the valley through a great aquaduct. Court rulings and actions by the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power have helped restore fish habitat along the river, making it again one of the finest fly fishing streams in the West.

The headwaters of the Owens River originate about 7-miles north of the town of Mammoth Lakes in an area that is now a protected wilderness. Located east of a relatively low elevation ridge of the Sierra Crest, precipitation from storms that arise in the Pacific fall or funnel into the high alpine meadows here. Seeps and springs create perennial wet meadows and these sustain one of the richest riparian habitats in the Eastern Sierra. The abundance of water overflows and is naturally channeled into the beginning of the Owens River. For about the first 6.5-miles of its origin, the Owens River and its two nearby tributaries, Glass and Deadman Creeks, hold the designation of Wild & Scenic River System.

This river, although relatively short at 183 miles, compared to the major rivers of the USA, has a long and legendary history. It flows through two of the major valleys of the southwestern Great Basin, Long Valley and the Owens Valley. It ends in the closed basin of the Owens Lake which is now largely dry. It is fed from its origin to its terminus by the enormous drainage of the Sierra Nevada.

Water is the essence of life and this river has sustained populations here for centuries. The region was inhabited by seminomadic Native Americans thousands of years ago. Evidence of their early hunter-gather culture has been documented in the traces of their sophisticated irrigation systems that were built to sustain small, efficient croplands.

The river has been the source of life and inspiration for explorers and settlers since its modern-day discovery in the early 1800s. Its importance is far more significant than many people know and understand. It is more than just a river that runs through an otherwise dry, semi-arid valley. It is the giver of life to millions. It is a significant contributor to sustaining the lives and lifestyles of millions of California residents today. Since the early 1900s much of the water from this revered river system has been redirected to supply the needs of Southern California. That’s different story for another time.

The entire system is world renowned as a premier fishing destination; from the sweeping bends of the river along the valley floors, to the high-altitude streams that tumble down the mountainside, to the reservoirs that hold the constant flow of water. Over 95% of the region through which this river flows is protected and has remained sparsely populated. The Eastern Sierra is a mecca for outdoor recreation and the Owens River is central to its status.

395 Travel on the Other Side of California

As you travel U.S. Highway 395 You’ll hear how a Slim Princess found her way to the Eastern Sierra and other fascinating stories from people who live along US 395.

Bishop

The most populated town in Inyo County, Bishop also has the most number of accommodations and services. Bishop began as a ranching town. Later, ranches evolved into pack stations with their sure-footed mules carrying the gear of fishermen and campers back into the Sierra. If any animal expresses the heart of Inyo County, it is the hard-working, intelligent , yet stubborn mule, which is honored annually during Bishop’s “Mule Days.” Long before the ranchers arrived, Paiute Shoshone people lived here. Their reservation sits northwest of town and the Paiute Palace Casino adds excitement to a stay in Bishop. Many of Bishop’s visitors include a stop at the Owens Valley Paiute Shoshone Cultural Center and Museum to learn about the first inhabitants of the area and to enjoy experiencing one of the tribe’s cultural events. Not to be missed on a visit to Bishop are Schat’s Bakery, Law’s Railroad Museum and Mahogany Meats. Schat’s Bakery is a traditional stop for travelers looking for a loaf of authentic “sheepherder’s bread” or any of their delicious baked goods. Mahogany Meats at the north end of town specializes in cowboy jerky and other smoked meats. The Law’s Railroad Museum is a collection of railroad equipment and buildings from Bishop’s days as a railroading center, shipping agricultural products from the Owens Valley north to the mining camps of Aurora and Bodie. Farming and ranching declined in the valley after water rights were acquired by the City of Los Angeles. Today, Bishop is the center of operations for the largest public utility in the nation, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, which provides water and power to the nation’s most populated city and provides access to the streams it manages for fishing.

Big Pine

This small town prides itself in having a big backyard. Big Pine is a portal to exploring both the Sierra Nevada and White Mountains. Drive east and you find the ancient Bristlecone pine. Drive west and you find trailheads that lead to the Palisade Glacier and Eastern Sierra. Outfitters run horse packing trips to remote alpine lakes. Numerous fishing holes are found along Big Pine Creek and the Baker Ponds. The Owens River teems with trout, catfish and bass.

Independence

The county seat since 1866, Independence is the center of regional history with its historic courthouse; the Edwards House, oldest structure in the county; the Commander’s House, a century-old Victorian home; the Mary Austin home (she wrote Land of Little Rain); Dehy Park that displays Slim Princess No. 18, a narrow-gauge engine; and the Eastern California Museum, with its extensive exhibits, artifacts, photographs, native plant garden and historic mining and farm equipment. Good fishing is found nearby at Independence Creek, the Onion Valley and along the Owens River. An early trout opener each March. With a name like Independence, it’s understandable why the town has one of the best Independence Day parades with traditional early morning flag raising, pancake breakfast, fun run/walk, small-town parade, homemade ice cream and pie social, kids’ games, an arts and crafts show, deep-pit barbecue and sunset fireworks show.

Lone Pine

One of the most filmed and photographed landscapes in the county is found surrounding Lone Pine. West of town are the Alabama Hills, named by locals who were Southern sympathizers during the American Civil War. This collection of irregular, ruddy, windswept boulders backed by a horizon of Sierra peaks, has been the backdrop for countless Hollywood films from Gunga Din, to Gladiator, to Rawhide, to How the West Was Won. It’s where Roy Rogers first mounted Trigger, where Tom MixLone Pine has been se en in so many movies, that it has commemorated its fame by hosting the annual Lone Pine Film Festival. The Museum of Western Film History preserves the motion picture history of Inyo County with film memorabilia, cars, western carriages and an 84-seat theater.

Manzanar National Historic Site – During World War II, people of Japanese ancestry, including American citizens were brought here to the Manzanar War Relocation Center. An interpretive center is located in the camp’s former auditorium. Audio tours are available.

South County

Pearsonville – You’ve arrived in Inyo County, if traveling north on US 395 in a town often called the “Hub Cap Capitol of the World,” thanks to Lucy Pearson who for years collected a large collection of hubcaps and cataloging and storing each in a large warehouse. In Pearsonville, you’ll find gas, food, a towing service, wrecking yard and a ton of hubcaps!

Keeler – This was once the southern terminus of the Carson & Colorado Railroad. When service ended in the 1960s, most of Keeler’s residents moved away. The streets are mostly quiet and no services exist. However, if you have a 4WD vehicle, follow a dirt road east to Cerro Gordo, a ghost town with several well-maintained silver mine buildings and a small museum.

Olancha – This little ranching town has been a waystation since its inception in the 1860s. Cooling cottonwood trees and an inviting café attract travelers along US 395. Hikers and backpackers will often set off into the South Sierra Wilderness and onto the Pacific Crest Trail from nearby trailheads.

Darwin – Stop in Darwin and you won’t find any services, just a rich history and Darwin Falls which begins as an underground spring that rises to the surface, spills over the falls and travels for a few hundred feet before disappearing again. Poke around Darwin and you’ll find old mines off dirt roads leading from CA-190.

>> More on Natural History of the Owens Valley written by Gigi DeJong

A Chronology of Key Events

THE CITY OF LOS ANGELES AND THE OWENS VALLEY

PREPARED BY THE INYO COUNTY WATER DEPARTMENT

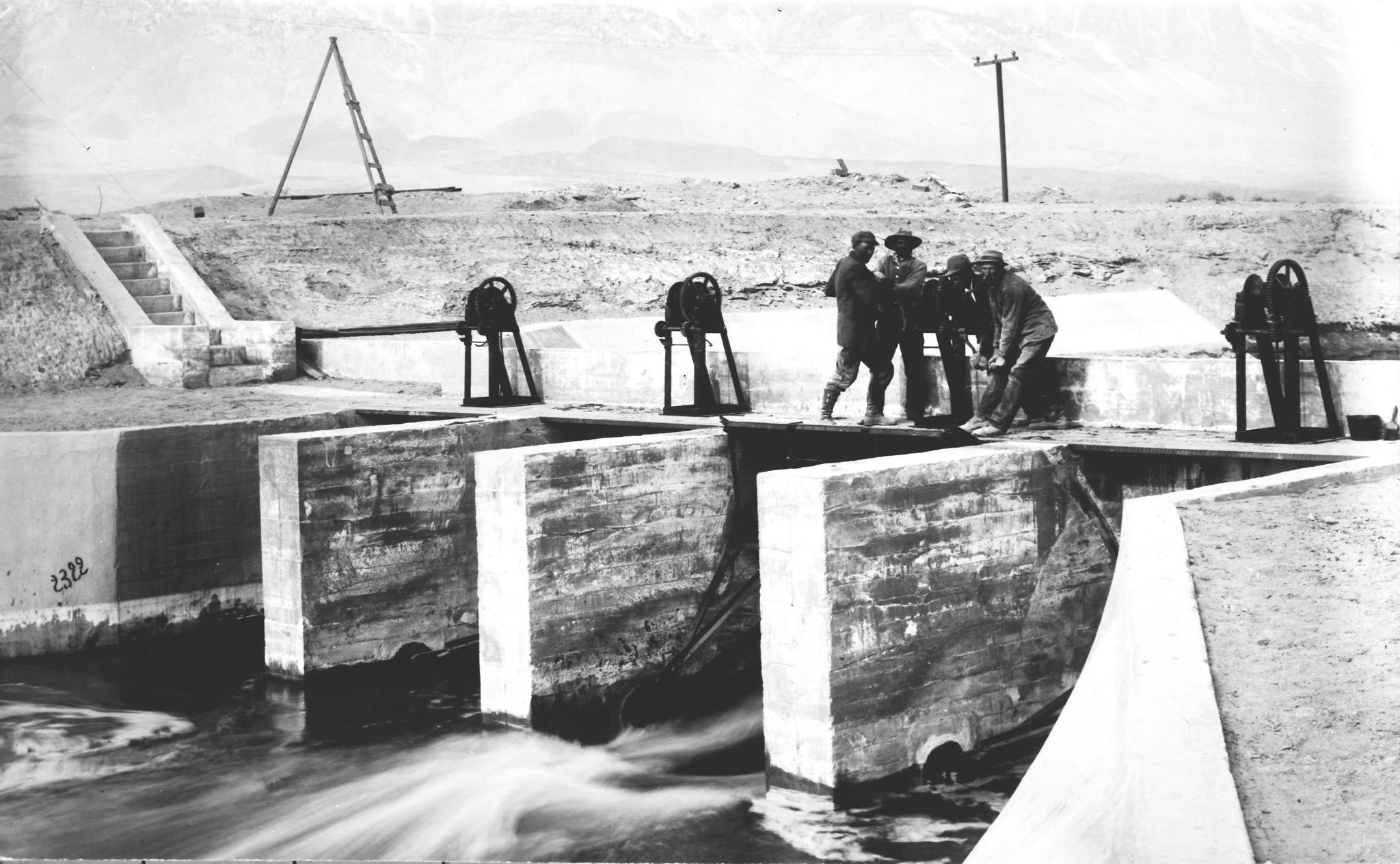

1902 The Reclamation Act is enacted by Congress and planning begins on a federal reclamation project in the Owens Valley for irrigation of as much as 185,000 acres.

1905 Los Angeles Water Commission approves plan for an aqueduct from the Owens Valley to the City of Los Angeles. City of Los Angeles begins acquisition of land and water rights in Southern Owens Valley downstream of the proposed aqueduct intake dam. Plans for a U.S. reclamation project in the Owens Valley are abandoned.

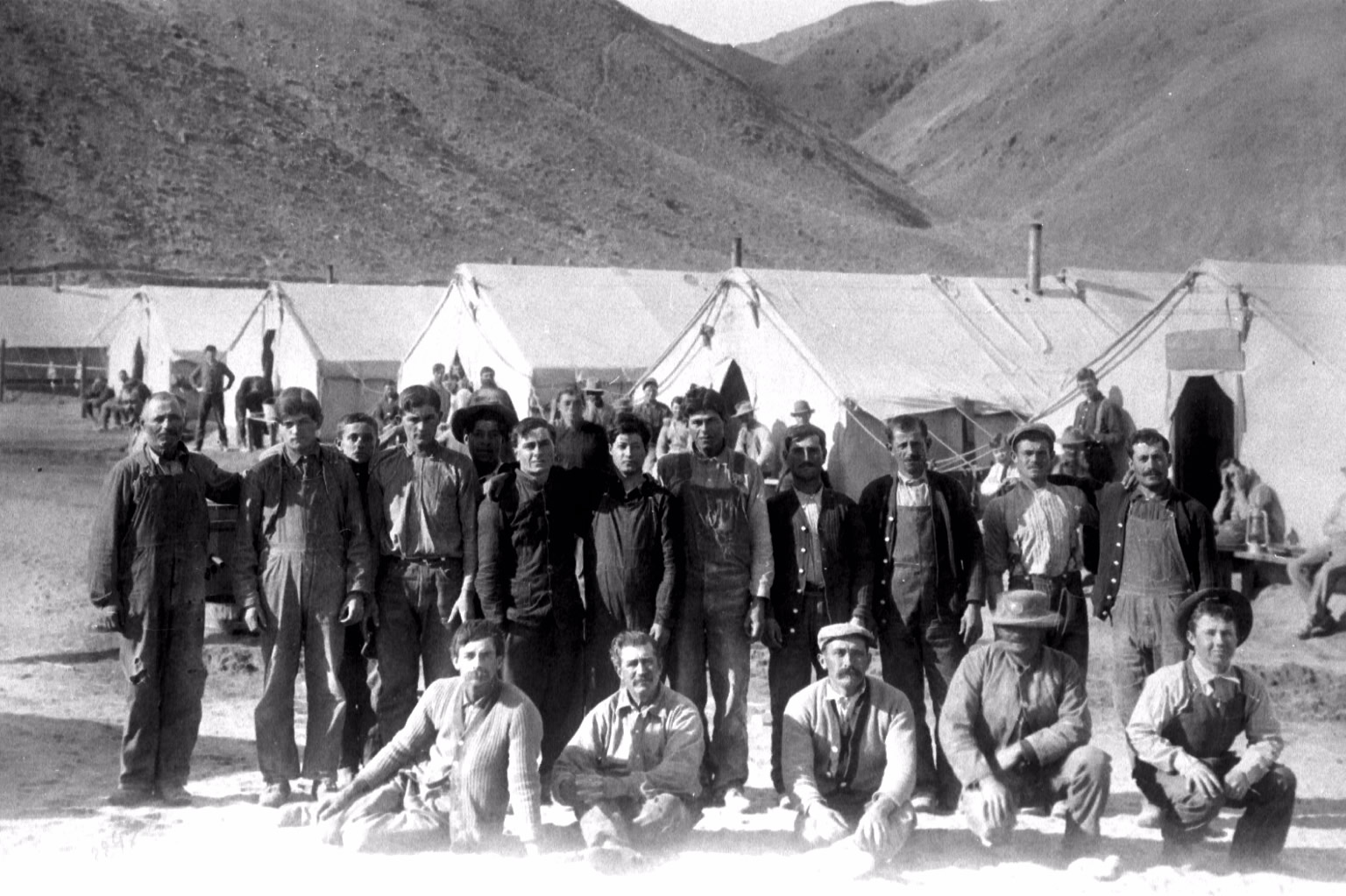

1905 Construction of the Los Angeles Aqueduct is commenced.

1913 LADWP completes aqueduct and begins the export of water from the Owens Valley to Los Angeles by diverting the water from 62 miles of the Owens River. The capacity of the aqueduct is approximately 480 cfs (300,000 acre feet per year).

1914 The State Constitution is amended to allow taxation of property owned by cities and other entities outside of their boundaries. (Land owned by Los Angeles in Owens Valley becomes taxable under the amendment.)

1924 Owens Lake becomes a dry lake bed as a result of Los Angeles’s diversion of the Owens River. Los Angeles announces program to purchase farm land and water rights in the valley that it had not already purchased. (Prior to the commencement of these purchases, Los Angeles has assured the residents of the valley that it would only purchase land and water rights downstream of the aqueduct intake dam.)

1924-30 Residents of the Owens Valley oppose Los Angeles’s land and water rights purchases and water exports. Violence sporadically occurs.

1925 Merchants demand reparations for loss of business due to Los Angeles’ purchase of the valley’s farm lands; in response, a state law is passed that allows Los Angeles to purchase properties in towns. Los Angeles announces that it would purchase any commercial, residential or agricultural property offered for sale. (By 1933, Los Angeles has purchased 85 percent of the valley’s residential and commercial property and 95 percent of the valley’s farm and ranch land.)

1934 Los Angeles files water rights application for 200 cfs of water from the Mono Basin and commences construction of an 11-mile underground water tunnel to hydraulically connect the Mono Basin with the Owens River.

1938-44 Los Angeles begins selling properties in valley towns directly back into private ownership (not at auction)–but without the associated water rights. (By

1944, approximately 60 percent of the town properties–1,240 parcels–have been sold.) Los Angeles and the U.S. Government complete negotiations of an Indian Exchange Agreement in which lands occupied by Native Americans were exchanged for Los Angeles-owned lands near Bishop, Big Pine and Lone Pine. The exchanges did not include water rights, but Los Angeles agreed to supply 5,556 acre-feet of water to the exchanged lands.

1940 Litigation brought by landowners over the effects of Los Angeles’ groundwater pumping in the Bishop area is ended by the entry of a court order commonly called the “Hillside Decree” which prohibits Los Angeles from pumping and exporting groundwater from an area around Bishop labeled as the “Bishop Cone.”

1941 Los Angeles completes construction of Mono Craters Tunnel and begins water diversions from Mono Basin. Construction of Long Valley Dam is completed and the reservoir (now known as Crowley Lake) begins to fill.

1944 Los Angeles ceases direct sales of town lands in the valley on the advice of the City Attorney that direct sales are illegal.

1945 Charles Brown Act is enacted which requires Los Angeles to grant existing tenants of its land in Inyo County the first right of refusal on lease renewals and land sales.

1947 Los Angeles resumes sales of its Owens Valley town properties at public auction (without water rights).

1952 LADWP diverts the river from the Owens River Gorge (downstream of Long Valley Dam) to produce hydroelectric power.

1957 Fish and Game Code §5937 is adopted which requires the owner of a dam to release sufficient water below the dam to keep fish below the dam in good condition.

1950s – 60s Los Angeles repeatedly challenges Inyo County’s tax assessments of its properties in Owens Valley.

1963 LADWP announces its plan to construct a second aqueduct from the Owens Valley to Los Angeles.

1963-68 LADWP reduces amount of irrigated lands in the Owens Valley in order to make additional water available for export through the second aqueduct.

1968 The California Constitution is amended to change the manner of assessment of Los Angeles-owned property in Owens Valley and to prohibit Inyo County from taxing water exported from Owens Valley. Under the new assessment procedure called the “Phillips formula,” the assessment of Los Angeles-owned lands in the valley is annually adjusted based on changes in the per capita assessed valuation of all properties in the state.

1970 In June, the Second Los Angeles Aqueduct is completed. The capacity of the Second Aqueduct is approximately 300 cfs (200,000 acre-feet per year). The combined capacity of the first and second aqueducts is approximately 780 cfs (570,000 acre-feet per year).

1972 Los Angeles announces plans to permanently increase groundwater pumping above the amounts that it disclosed prior to and during the construction of its second aqueduct. The sources of water supply to the Second Aqueduct are:

- Increased groundwater pumping from Owens Valley,

- Decreased irrigation in Owens Valley, and

- Increased diversions from Mono Basin.

Five months after the completion of the Second Aqueduct, the California Environmental Quality Act (“CEQA”) is enacted.

1972 In December, Inyo County commences CEQA litigation against Los Angeles seeking the preparation of an EIR on the Second Aqueduct and a halt to Los Angeles’s increased groundwater pumping.

1973 Third District Appellate Court (located in Sacramento) issues a writ commanding Los Angeles to prepare an EIR on the water supply for the Second Aqueduct. (Although the Court acknowledged that construction of the Second Aqueduct had been completed by the effective date of CEQA, it found that the water supply to the Second Aqueduct was a project subject to CEQA.)

1973-1984 The Appellate Court restricts groundwater pumping by Los Angeles to 149 cfs (108,000 AF/Y) pending Court approval of an LADWP EIR on the water supply for the Second Aqueduct.

1977 Based on a challenge by Inyo County, LADWP’s EIR on the water supply for the Second Aqueduct is found inadequate by the Appellate Court.LADWP cuts water supplies to Owens Valley ranchers. Inyo County obtains order from Appellate Court requiring water supply to be restored.Due to severe drought, upon application by LADWP, Appellate Court allows LADWP to pump up to 315 cfs after LADWP. At the urging of the Inyo County, the Court makes the increased pumping contingent upon Los Angeles adopting the first water conservation plan for the city.

1979 The Charles Brown Act is amended to permit the sale of leased Los Angeles-owned property at public auction if the lessee has requested such a sale 30 days in advance. The California Supreme Court rules that the public trust doctrine applies to Los Angeles’ diversions from the streams tributary to Mono Lake and orders that Los Angeles water rights in the Mono Basin be reconsidered in light of the public trust doctrine.

1980 The Inyo County Board of Supervisors submit an Owens Valley Groundwater Management Ordinance to County’s voters and the Ordinance is overwhelming approved. The Ordinance creates the Inyo County Water Commission and Inyo County Water Department. The Ordinance requires the Water Department/Water Commission to develop an Owens Valley water management plan and requires Los Angeles to obtain a permit from the County before it can pump groundwater from the Owens Valley.

1980 Los Angeles files lawsuits challenging the Groundwater Management Ordinance. In one case, LADWP successfully compels the County to prepare an EIR on its Owens Valley water management plan before the Ordinance can be implemented. In a second case (Inyo Superior Court Case No. 12908), LADWP challenges the legality of the Owens Valley Groundwater Management Ordinance.

1981 Based on a challenge by Inyo County, a second LADWP EIR on Second Aqueduct water supply is found inadequate by the Appellate Court.

1982 An MOU dated September 2, 1982 between Inyo County and LADWP, announces the County’s and LADWP’s intent to work together to identify and recommend methods to meet the needs of the valley and Los Angeles. The MOU creates the Inyo County/Los Angeles Standing Committee and Inyo County/Los Angeles Technical Group.

PROVISIONS OF THE 1982 MOU

- LADWP and the County intend to work together to identify and recommend methods to meet the needs of the Owens Valley and Los Angeles.

- The parties desire a groundwater study of the Owens Valley to be made by the USGS.

- A Standing Committee and a Technical Group is created. The Standing Committee is comprised of one member of the LA City Counsel, two members of the LADWP Commission, three LADWP staff members, at least one Inyo County supervisor, two Inyo County Water Commissioners, and three Inyo County staff members.

- The Standing Committee is to meet at least every two months to review recommendations from the Technical Group, to discuss and suggest resolutions to differences between the parties, to issue reports and to make recommendations.

- The Technical Group is comprised of not more than five representatives selected by the County and five representatives selected by Los Angeles.

- The County and LADWP each have one vote on the Technical Group and on the Standing Committee.

1983-89 The USGS conducts groundwater and vegetation studies in the valley.

1983 In a ruling in Inyo County Superior Court Case No. 12908, the Court finds the County’s Groundwater Management Ordinance unconstitutional and preempted by state law.

1983 California Supreme Court rules that the “Public Trust Doctrine” applies to LADWP’s diversions from streams that are tributary to Mono Lake.

SB 270 (Health and Safety Code section 42316) is enacted authorizing the Great Basin Unified Air Pollution Control District to require Los Angeles to provide reasonable mitigation of air quality impacts associated with its water gathering activities.

1984 Los Angeles and Inyo County reach “interim” groundwater management agreement. One goal of the interim agreement is for LADWP and the County to reach a “long-term” water agreement. Under the interim agreement, LADWP provides limited funding to County for water-related activities and LADWP’s groundwater pumping is cooperatively managed by LADWP and the County. Appellate Court lifts its groundwater pumping restriction of 149.56 cfs and instead allows the County and LADWP to implement groundwater management under the interim agreement; however, the Appellate Court issues a writ requiring that the impacts of any “long-term” water agreement between Los Angeles and the County, as well as the impacts of LADWP’s groundwater pumping since 1970, be addressed in an EIR.

1985-1991 Under interim agreements, LADWP’s groundwater pumping is cooperatively managed by Inyo County and LADWP.

1989 The County and LADWP reach a preliminary agreement on a long term water agreement. Under the preliminary long-term agreement, “ON-OFF” groundwater pumping management is implemented in the fall of 1989. The preliminary agreement is released for public review.

The Court of Appeal rules that Los Angeles’ water rights licenses to divert water from streams in Mono Basin must be amended to require a bypass of water for fishery protection under Fish and Game Code section 5937 et seq.

1990 In a test of the Water Agreement, three County supervisors are recalled, but are retained in the election.

1991 The Court of Appeal rules that Los Angeles’ water rights licenses in Mono Basin should be further amended to require a bypass of water sufficient to maintain the fisheries that existed prior to Los Angeles’ stream diversions.

1991 An accidental rupture of a pipe supplying Los Angeles’s hydroelectric plant causes water to begin flowing in the Owens Gorge. Mono County and the California Department of Fish and Game, under Fish and Game Code section 5937, sue to require a permanent flow in the gorge to protect the fish. Los Angeles agrees to maintain flows in the gorge. In October, 1991, Los Angeles and Inyo County approve “Long Term Water Agreement” and certify the 1991 EIR that addresses the environmental impacts under the Agreement and the environmental impacts of LADWP’s groundwater pumping since 1970.